Eliminating the “Balance Wheel Metaphor” in the Wake of COVID-19

By Kristin D. Hultquist

As COVID-19 continues to impact students, teachers, families, colleges, and universities across the country, HCM Strategists is working to provide essential thought leadership on the range of issues in the field of education.

Our expert policy staff has launched a new series to identify emerging education policy ideas and practices aimed at addressing COVID-19. Stay tuned for more in HCM’s new series addressing COVID-19 concerns in education, and use #EdAfterCOVID19 to join the conversation on social media.

Six weeks into a near-total shut down of major sectors of the U.S. economy and at least 30 million Americans have lost their jobs. To date, the federal government has spent 10% of its annual GDP to compensate for the economic losses and direct expenses of managing the pandemic. State revenues are in free-fall. In states across the country, budget committees are asking agencies to plan for 20% cuts in the next fiscal year budget, including public higher education. Colleges have begun the predicted budget-cutting measures: freeze travel and new hiring, stop all planned new spending, halt planned pay increases, cut pay, furlough or lay off employees.

Richard Florida, an urban expert and economic development adviser to cities across the globe, told those of us “gathered” by the Downtown Denver Partnership last week that the strongest assets for economic recovery are: 1) our international hub airport; 2) our colleges and universities; 3) our downtown. The COVID-19 recovery path he laid out showed the imperative of supporting these assets. What Dr. Florida did NOT say, and rightfully so, is that Colorado should use higher education funding as a balance wheel.

Twenty years ago, the late Hal Hovey coined the expression “higher education is the great balance wheel in state budgets.” It means higher education is cut deepest to balance state budgets during economic downturns. Ever since my colleagues specializing in postsecondary finance have used the term to foreshadow the cuts and slow recoveries that would accompany recessionary periods.For state economies to rebound in ways that are more inclusive and prosperous in FY2021, higher education budgets need to improve the rate of return. Any money states spend on higher education and worker training needs to prioritize the changes and outcomes we need. This includes more productivity, flexibility in delivery, holistic supports delivered virtually, affordability and more credentials earned. Even budget cuts should reflect the need to improve the rate of return. Where and how much we invest in higher education over the next 24 months will help determine how the nation’s economy and our most vulnerable rebound from this crisis.

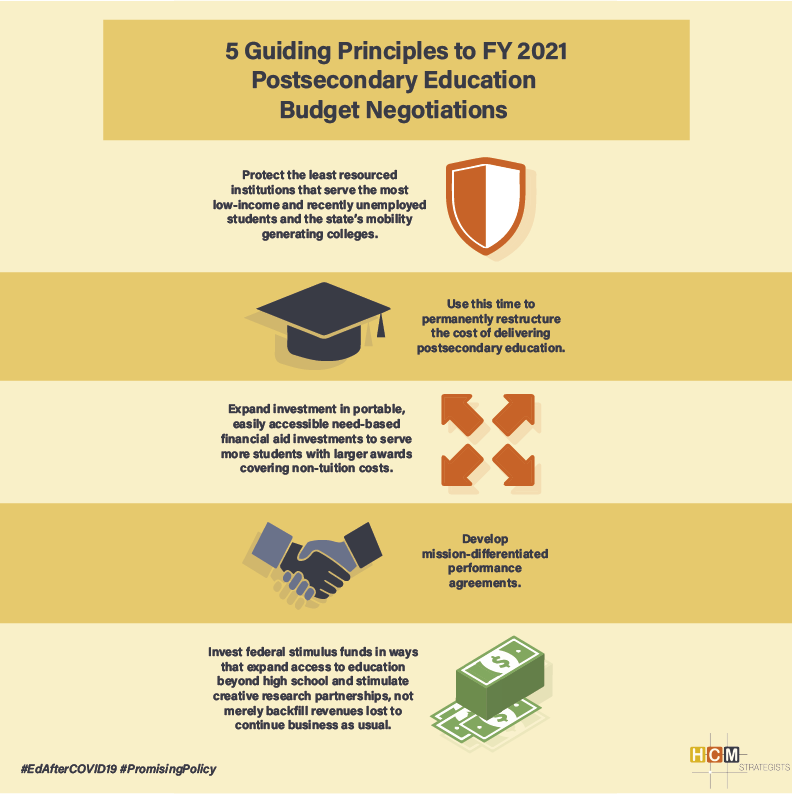

Protect the least resourced institutions that serve the most low-income and recently unemployed students and the state’s mobility generating colleges. Make no flat across-the-board cuts, which maintain funding inequities between the most selective, highly-resources institutions and the less selective, fewer resources colleges. Community, technical and regional public colleges are the state’s workhorses when it comes to educating low-income students as well as a greater share of the state’s residents, who stay and work in the state after completing programs.[1] These providers lead the way in producing upward mobility for its graduates.[2]

Expand investment (yes, increase spending in this COVID-19 era) in portable, easily accessible need-based financial aid to serve more students with larger awards covering non-tuition costs. Beyond helping students continue to afford their education and training, this targeted investment creates necessary financial incentives for providers to recruit and retain those students for whom a postsecondary credential of value will make the greatest difference in terms of economic return to the state.

Develop mission-differentiated performance agreements whereby short-term bridge loans (potentially forgivable), regulatory and policy moratoriums and special allocations from state rainy day funds are offered in exchange for needed improvements in academic and administrative productivity, credential partnerships with industry and equity protections (e.g., double down on the commitment to enrolling and serving Pell Grant students and students of color; negotiate with higher education segments seeking tuition increases to ensure parallel increases in the number of Pell students they enroll with the full cost of attendance financial aid packages).

Use this time to restructure permanently the cost of delivering postsecondary education. States should invest in colleges that are willing to examine all revenue streams and expenses. Early COVID-19 responses thus far indicate the need to examine all costs campus-wide. There is also an indication for the need to embrace systemwide digital advising, transition on-line and hybrid instruction as required elements of al students’ postsecondary paths, embrace transfer policies that value all learning and govern and manage institutions based on core productivity metrics.

Invest federal stimulus funds in ways that expand access to education beyond high school and stimulate creative research partnerships, not merely backfilling lost revenues to continue business as usual. With hundreds of campus closures anticipated over the next few years, states need to proactively create and expand on-line, short-term programs, increase broadband access and shared services platforms and combine state, federal, and private sector funding for Tier 1 research institutions’ medical research.

COVID-19 led to a pause in American life with an extensive recovery period for the foreseeable future. In postsecondary finance, let’s now pivot to use the tools of budgets, loans, and stimulus funds to invest in higher education like the great economic recovery asset it is.

References:

[1] In her work for Lumina Foundation’s Commission on Financing 21st Century Postsecondary Education, Harvard’s Dr. Bridget Terry Long examined the distributions of state appropriation by institution type. She found a consistent 25-year gap of 2.45 times higher state appropriations for the former.

[2] See Raj Chetty’s work on colleges with the highest mobility rates: https://opportunityinsights.org/paper/mobilityreportcards/ (or non-technical summary here: https://opportunityinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/coll_mrc_summary.pdf).